- Home

Edition

Africa Australia Brasil Canada Canada (français) España Europe France Global Indonesia New Zealand United Kingdom United States Edition:

Global

Edition:

Global

- Africa

- Australia

- Brasil

- Canada

- Canada (français)

- España

- Europe

- France

- Indonesia

- New Zealand

- United Kingdom

- United States

Academic rigour, journalistic flair

Academic rigour, journalistic flair

medea sandys a f a.

Thrilling new versions of Greek myths pulse with queer desire and feminist fury

Published: December 9, 2025 7.09pm GMT

Rachael Mead, University of Adelaide

medea sandys a f a.

Thrilling new versions of Greek myths pulse with queer desire and feminist fury

Published: December 9, 2025 7.09pm GMT

Rachael Mead, University of Adelaide

Author

-

Rachael Mead

Rachael Mead

Fellow, J.M. Coetzee Centre, University of Adelaide

Disclosure statement

Rachael Mead does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Partners

University of Adelaide provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

DOI

https://doi.org/10.64628/AA.e9mhechxf

https://theconversation.com/thrilling-new-versions-of-greek-myths-pulse-with-queer-desire-and-feminist-fury-266079 https://theconversation.com/thrilling-new-versions-of-greek-myths-pulse-with-queer-desire-and-feminist-fury-266079 Link copied Share articleShare article

Copy link Email Bluesky Facebook WhatsApp Messenger LinkedIn X (Twitter)Print article

Stories from the ancient past are enjoying a literary renaissance. Classicist, broadcaster and comedian Natalie Haynes stands out for her ability to straddle scholarship and storytelling. The international success of her classical fiction and nonfiction speaks to readers’ fascination with examinations of myth and contemporary retellings that peel away centuries of cultural, gender and identity bias.

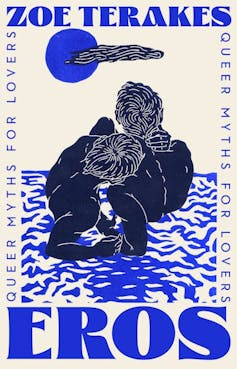

And in a thrilling entry into the ever-evolving genre of mythological retellings, Australian writer, actor and trans/queer advocate Zoe Terakes revisits five ancient tales through a defiantly queer lens, in their debut short-story collection, Eros: Queer Myths for Lovers.

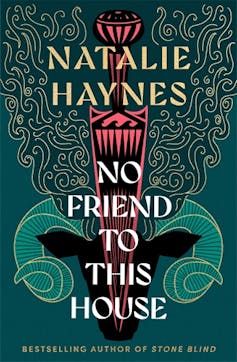

Review: No Friend to This House – Natalie Haynes (Pan Macmillan); Eros: Queer Myths for Lovers – Zoe Terkaes (Hachette)

These two books interrogate the myths of the ancient world, stripping away centuries of patriarchal and heterosexual assumptions about the definition of heroism. Familiar stories are told from new perspectives.

In her fifth novel, No Friend to This House, Haynes continues her mission to wrest the focus of ancient Greek myth away from the male hero.

This time, she turns to one of antiquity’s most enduring tales: Jason’s quest for the Golden Fleece. Apollonius of Rhodes’ book Argonautica is often used as the historical source for the story of Jason, leader of the Argonauts, and Medea, the sorceress who helped him take the Golden Fleece from her father – then married him. But Haynes widens the frame, in narrative voice and scope.

Decentring Jason and his band of Argonauts, she hands the story to the women and minor figures of the myth. This includes Medea’s murder of their two sons, after Jason leaves her for another woman. Haynes allows those sidelined and victimised by Jason’s quest to speak. Using her signature multi-voiced structure, Haynes creates a chorus of perspectives from those relegated to the periphery by ancient sources.

With wit and sardonic insight, this cast of narrators reveals the impact of the “heroes” choices, as the expedition moves from Jason’s hometown Iolkos to his destination Colchis, home of the Golden Fleece – and back.

Goddesses, naiads and nymphs

Female voices dominate: women, goddesses, naiads and nymphs. Together, they tell their stories of abandonment, fury and despair. But Haynes pushes further, insisting we move beyond the human perspective. Jason’s ship, the Argo, speaks, as does the bird who guides the Argonauts through the clashing rocks, and the golden ram whose hide is flayed to become the famous golden fleece.

These non-human voices reframe the quest as an act of violence and disruption, extending beyond the Argonauts and their human victims.

More intriguingly, the quest itself is freed from its traditional boundaries. Instead of beginning with Jason’s challenge from his uncle, King Pelias, to steal the fleece from Colchis (at the eastern end of the known world), Haynes makes us reconsider where this story truly starts and ends. It reaches back to its origin: Helle and Phrixus (children of Nephele, goddess of clouds) escaping their stepmother Ino on the back of the golden ram. It also stretches forward, past Jason’s triumphant return to his family.

Drawing on Euripides’ Medea and Ovid’s Heroides, Haynes casts fresh eyes on one of mythology’s most demonised women. Her re-examination of Medea is signalled in the chapter epigraphs: each is a line (translated by Haynes herself) from the opening of Euripides’ play. Historically, most classical translations have been produced by men. The first verse translation of The Odyssey by a woman, Emily Wilson, only appeared in 2017. So Haynes’ decision to personally translate Euripides’ Ancient Greek is a powerful declaration.

Natalie Haynes is on a feminist mission to strip centuries of cultural, gender and identity bias from ancient myths.

Pan Macmillan

Natalie Haynes is on a feminist mission to strip centuries of cultural, gender and identity bias from ancient myths.

Pan Macmillan

Medea is not exonerated

Her broader project is to reexamine these stories and strip away centuries of accumulated bias – across both fiction and nonfiction. Given Haynes’ feminist lens, it would be easy to assume she might apologise for Medea’s crimes. Instead, she offers a complex portrait.

Medea is not exonerated. She is rendered in full: daughter to a tyrannical father, refugee, magic-user – and a political strategist keenly aware of her power and vulnerability. By giving voice to Medea and the women around her, Haynes exposes Jason’s unheroic actions in the years following the quest – such as taking another wife while still married to Medea, threatening to take the children and render her homeless. Yet she equally scrutinises Medea and her choices.

The result is not an attempt to justify Medea’s actions, but an exploration of how a person – flawed, furious, capable of the unimaginable – might still be profoundly human.

Extending the story and handing it to so many voices creates a challenge in maintaining narrative tension. But the resulting chorus is consistently fascinating, and the cast list in the front of the book proves invaluable for situating the more obscure players. For readers drawn to Medea – the dark magnet at the heart of this story – her delayed arrival, a third of the way into the tale, might feel like a long wait. But the voices who lead us there bristle with more than enough anger, betrayal and conflict to drive it in the meantime.

No Friend to This House is another sharp feminist reclamation from Haynes. The novel dismantles the heroic epic and engages with ancient sources in ways that are witty, yet grounded in the emotional heft of this tragedy. It is Haynes’ most challenging (arguably, her most controversial) subject. But it is also one of her most successful – less a retelling than a dismantling of Jason’s legend. It rebuilds the myth through the voices of those left in the margins.

Queer myths for lovers

In Eros: Queer Myths for Lovers, Zoe Terakes mines their Cretan ancestry and trans experience to centre identities long pushed to the margins of the mythological record. They refuse both the heterosexual straightening and the hero worship that have fossilised these stories over the centuries.

Zoe Terakes.

Zoe Terakes

Zoe Terakes.

Zoe Terakes

Terakes’ myths range from the canonical to the unexpected. The opening story reimagines the love between Iphis – born female, raised and disguised as male (to avoid being killed by their father) – and childhood friend Ianthe, praised for “her unequalled beauty”.

The story, familiar to many from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, is sharpened into something far more visceral and urgent. Told from Iphis’ perspective, Terakes reframes the tale as a narrative of trans masculinity, stripping back centuries of sentimentality to reveal a character wrestling with their hidden identity.

In the second story, Icarus, who flew too close to the sun with wax and feather wings, is freed from his conventional role in the cautionary tale about arrogance. His story is reimagined as a study of homoerotic longing between a mortal youth and a god.

The third piece is set in the contemporary underworld. Eurydice, whose husband Orpheus famously tried to bring her back from the dead, is recast by Terakes as a dissatisfied girlfriend who uses her death to break free from her traditional passive fate and claim agency during her time in the afterlife.

And in the final two stories, the location migrates from ancient Crete to late 20th-century Australia. Terakes again takes fascinating liberties with myth.

They twist the myth of Artemis, goddess of wild animals and the hunt, and the nymph Kallisto, tricked into sleeping with Zeus and turned into a she-bear as a result. Artemis and Kallisto’s relationship plays out in a fantastical tale of migration and family loyalty that veers from a magical Cretan setting to a sweaty Northern Rivers abode, both revolving around a Zeus-like father-figure raised by a goat.

Hermaphroditus, a youth who in myth became both male and female due to the unrequited passion of an enamoured nymph, experiences the shock of transformation in the humid, neon-lit underworld of King’s Cross.

Hermaphroditus (left)

Louis Finson/Wikimedia

Hermaphroditus (left)

Louis Finson/Wikimedia

Like Haynes, Terakes writes with a keen awareness of the centuries of scholarly varnish applied to the mythological record by classicists who are overwhelmingly white, male and (at least presenting as) heterosexual. This varnish has obscured, minimised or erased queer identities. Of course, queer love, much like other minority perspectives, has always existed: Terakes re-examines these stories through a queer lens as an act of reclamation – a restoration, rather than invention.

Since Madeline Miller’s wildly successful The Song of Achilles (2011) opened the door for queer love in the mythological retelling genre, these stories have increasingly honoured – and at times amplified – non-heterosexual voices. Terakes extends this project with authority.

As a trans man and prominent queer advocate, they write these characters with a confidence that is intimate, visceral and boldly political.

Sweaty, urgent, sensual and raw

One of the many pleasures of reading ancient literature is the sense of emotional connection it offers to lives from the deep past – the recognition those who lived millennia before us loved, grieved and yearned with the same ferocity we do.

Terakes pushes this identification even further, slipping readers not only into the emotional lives of these characters, but into their erotic ones too. These first-person narratives are intensely embodied – sweaty, urgent, sensual and raw – capturing not just the lust and longing, but the comedown after it.

Terakes’ writing style slides between the mythic and the modern. In the story of Icarus and Apollo, they show us Icarus’ first glimpse of the minotaur:

And there he saw it. Steaming with unnatural heat. Hot out of hell. The bull. Bloodied pearlescent horns mounted its large, bovine head. Its eyes were tunnels, a kind of black that didn’t occur in nature. They were the colour of death – impenetrable, unendurable.

But soon, the writing switches from this epic tone to the vernacular. The Cretan queen confesses to bestiality, spitting: “I fucked him […] And it was wonderful.”

The pieces set in the contemporary world weave in commentary on the migrant experience and Australian racism. It’s unusual, but not jarring, in a collection that deftly straddles millennia. Terakes’ insistence on bringing queer sexualities into mainstream literature feels not just important, but vital.

The explicit eroticism of these stories may not be to the taste of all readers – but its presence within a genre committed to amplifying marginalised voices is essential. These myths always had desire at their core. Terakes is simply restoring identities that heteronormative scholarship had erased.

- Book reviews

- Greek mythology

- Medea

- Euripides

- Australian fiction

Events

Jobs

-

Senior Lecturer, Educational Leadership

Senior Lecturer, Educational Leadership

-

Respect and Safety Project Manager

Respect and Safety Project Manager

-

Associate Dean, School of Information Technology and Creative Computing | SAE University College

Associate Dean, School of Information Technology and Creative Computing | SAE University College

-

Senior Lecturer, Clinical Psychology

Senior Lecturer, Clinical Psychology

-

University Lecturer in Early Childhood Education

- Editorial Policies

- Community standards

- Republishing guidelines

- Analytics

- Our feeds

- Get newsletter

- Who we are

- Our charter

- Our team

- Partners and funders

- Resource for media

- Contact us

-

-

-

-

Copyright © 2010–2025, The Conversation

Senior Lecturer, Educational Leadership

Senior Lecturer, Educational Leadership

Respect and Safety Project Manager

Respect and Safety Project Manager

Associate Dean, School of Information Technology and Creative Computing | SAE University College

Associate Dean, School of Information Technology and Creative Computing | SAE University College

Senior Lecturer, Clinical Psychology

Senior Lecturer, Clinical Psychology